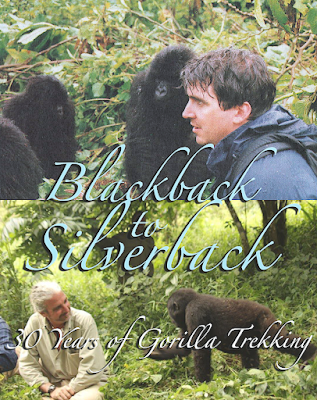

In my memoir, Gorilla Tactics: How To Save A Species (soon to be published in the United States by Chicago Review Press), I describe in detail the dramatic moment in October 1992 when I first came face to face with my hairy mountain cousins. Here's a short excerpt from my, as yet, unpublished manuscript:

The wind blasts a hole through the mist and for a moment we can see Lake Kivu and the town of Gisenyi a few thousand metres below us. We then find Group 5’s night nests. A forward tracker assures us over walkie talkies that the gorillas are not far. We descend into a saddle and are surrounded by giant lobelia plants. There is an unusual odour in the air, like a workman’s armpit after a hard day’s toil. Bob tells me it is a fear odour that gorillas give off when they sense danger. I imagine they can smell us too. They probably know I drank a barrel of banana beer last night. A gorilla is sheltering from the rain beneath a hagania tree. But for a faint reflection in his dark eyes when he briefly glances at us, his form is barely discernible in the faint light. He sits perfectly still. He will not move until the rain stops, or I cross a line. Bob makes a well-rehearsed guttural sound with his throat, known as a belch-vocalization, which in gorilla language means, “Everything’s cool.” More gorillas appear. I am relieved that we have found them. Rainfall facilitates our entry into their world. Around us the foliage glistens. Despite the high average rainfall in their habitat, by all appearances gorillas do not much like the rain. They remain stock still, shabby black forms huddled together, hardly even looking up.